On the extreme northern boundary of the parish of Lindridge flows the water course of Marlbrook. This was used to create a section of the Kington, Leominster, Stourport Canal which was partially opened in 1796, and a year later a ceremonial sod of earth was cut where the canal was to enter the Severn at Astley.

At the time, the agricultural areas of South Shropshire and North Herefordshire were suffering from poor transport facilities. This stopped the landowners from capitalising on the improvements in farming practices. Earlier attempts to make the rivers Teme and Lugg navigable had proved unsuccessful.

The original idea for the proposed canal was to be as an export route mainly to carry agricultural produce such as grain, flour, hops, cider and perry along with leather goods and timber. The only non-agricultural goods were local coal and stone from the rural areas of Herefordshire.

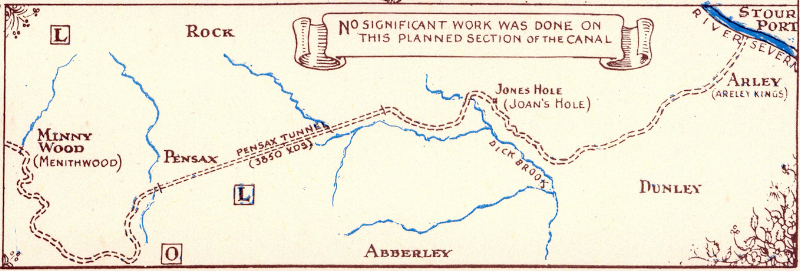

The canal was intended to provide a transport link from the rural towns of Kington, Leominster and Tenbury Wells to the navigable river Severn at Stourport. Boats could then enter the port where goods could be shipped on to the Staffordshire and Worcestershire canal. This canal had been built some twenty years earlier by the eminent canal engineer, James Brindley. The Staffs and Worcs canal ran due north linking up with the industrial towns of the West Midlands where more lucrative markets could be sought. On the return route manufactured goods could be imported into Shropshire and Herefordshire.

The chief engineer employed to oversee the project was a Thomas Dadford Jnr who had earlier assisted his father and brothers in the construction of the port at Stourport. Work began in earnest on the canal during the late 1780s, but progress was said to be very slow. During the subsequent years very little news of its progress is available. However by July 1796 the Putnal tunnel near Orleton had been completed as well as the river Rea aqueduct near Knighton-on-Teme, (which is said to have needed a million bricks in its construction). The river Teme aqueduct between Wooferton and Little Hereford was also completed.

The eminent Scottish engineer of the time John Rennie was called in to survey all three of these sites. He concluded that the Rea aqueduct was of poor construction, unsafe and wouldn’t stand the test of time. As to the Teme aqueduct, it had insufficient foundations. The problems encountered at the Putnal tunnel during its construction were due to poor management.

It has to be noted that the Rea Aqueduct, abandoned after the closure of the canal during the 1850s, and neglected ever since, still stands today (albeit in a very poor condition). It is a monument to the engineers who designed and built it. Only as recently as the 1990s the public right of way that crossed the aqueduct was declared unsafe and a restriction order put in place, but I am lead to believe that most walkers ignore the order and risk the consequences. The Teme aqueduct also still stands, although the centre span was deliberately blown up during the second world war as a precaution to hinder German troops in the event of a full scale invasion of Britain.

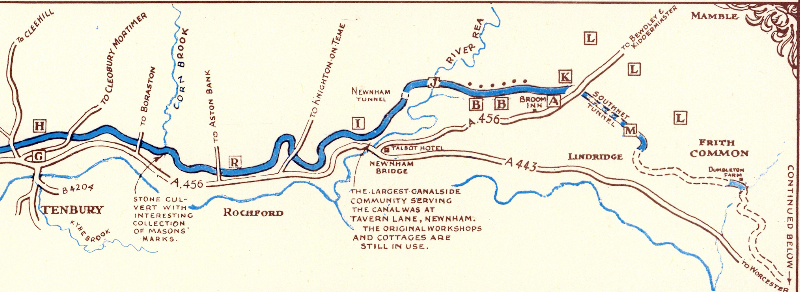

In 1796 a usable 18 mile section of the canal opened between Leominster and Broom Bank where coal wharfs had been built. The latter being the closest point of the canal to Sir Walter Blount’s coal mines at Mamble and Pensax. The coal was transported from the pit head by means of a plateway. Sir Walter, who resided at nearby Mawley Hall, was one of the original promoters of the canal. In fact out of the originally proposed 45 miles this is as far as the canal ever reached.

During June 1796 a boat bound for Leominster named The Royal George built by a Mr Bird of Stourport was launched at Tenbury. The British Chronicle reported “numerous people attended and the launch took place amid the firing of cannon, flag flying, music playing and other demonstrations of joy”. In December the same year 14 barges of coal from Thomas Blount’s pits arrived at Leominster wharf. The contents of the first boat were distributed free to the deserved poor and the remainder was sold at 15/- per ton. Prior to this the cheapest coal available at Leominster had cost 30/- per ton.

Meanwhile Southnet tunnel which was adjacent to Southnet Wharf had been completed, but disaster struck when the tunnel collapsed, and according to local legend two workmen became trapped and their bodies never recovered. The tunnel was never used and still lies abandoned. Some exploratory work was carried out at Brickyards field, Dumbleton which is adjacent to where the canal was to cross the Dumbleton brook. The site was filled in and levelled during the early part of the 20th century.

As early as 1881 the canal began to run into financial difficulties and all funds exhausted. Any further proposed work was put on hold. Two prominent engineers of the day were consulted on how to proceed with the completion of the proposed section to Stourport. Several ideas were considered but never got to the planning stage due to lack of funding.

However the 18 mile usable section of the canal managed to soldier on for another 50 years, relying mainly on monies gained by tolls from the transportation of coal from the Mamble pits. In 1845 discussions began to sell the canal. The following year it was sold to the Shrewsbury and Hereford Railway Company. Luckless shareholders only received 16/- for every £100 invested. It wasn’t until 1858 that arrangements were made to let off the water. In 1860 the S & H Rail Co sold the Wooferton to Newnham Bridge section (which happened to be the largest canalside community serving the canal). The buyers were the Tenbury Railway Company. It formed the branch line which eventually linked up with G.W.R. main line that ran between Bridgnorth and Bewdley.

As for the canal today, looking back with hindsight it may now seem to many observers a very ambitious and perhaps a foolhardy enterprise, given the very nature of the terrain that lay between Broom Bank and Stourport. Stairs of locks or tunnels were needed to access the ranges of hills that hindered its path. At close inspection much of the usable 18 mile route can still be traced today by using public rights of way. Many of the original canal related constructions can also still be seen.

Derek Marks, March 2011

The following images are extracts from a beautifully hand drawn and illustrated map of the proposed canal by Harold Barnes in about 1977.

Further reading

The Herefordshire Through Time section of the Herefordshire County Council website has a section on the canal here. (Note the two subsection links in the left hand navigation column.)